Toward using GANs in astrophysical Monte-Carlo simulations

Basic architecture of a Generative Adversarial Network

Basic architecture of a Generative Adversarial NetworkHigh-Level Overview

Accurate modeling of spectra from X-ray sources requires computationally expensive Monte-Carlo (MC) simulations. These simulations must sample from numerous complex probability distributions—a process that is a significant computational bottleneck.

This project explores using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to replace these time-consuming sampling steps.

The Challenge: Sampling the Maxwell-Jüttner Distribution

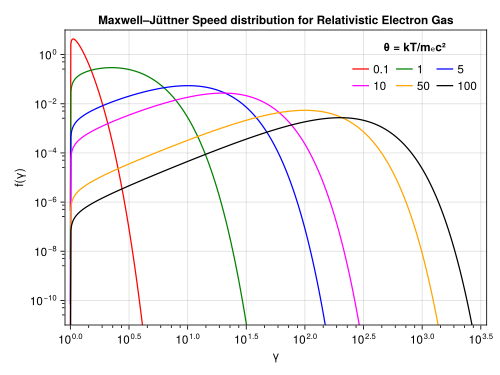

Our main goal was to replicate the Maxwell-Jüttner (MJ) distribution, a family of distributions used in astrophysics to describe the speed of relativistic electrons. This distribution is conditioned on a temperature parameter $T$. As we decrease $T$ it becomes increasingly more difficult to sample from the MJ distribution using known sampling methods like the Sobol rejection algorithm

The pdf is provided below:

$$ P_\mathrm{MJ}(\gamma)=\frac{\gamma^2\beta}{\Theta K_\mathrm{2}\left(1/\Theta\right)}\exp\left(-\frac{\gamma}{\Theta}\right)\, $$where $\gamma$ is relativistic Lorentz factor, $\beta=v/c$ is normalised velocity of an electron, and $K_\mathrm{2}$ is the modified Bessel function of the second kind. Lastly, $\Theta=k_\mathrm{B}T/(mc^2)$, where $T$ is the temperature of the gas, $k_\mathrm{B}$ is Boltzmann constant, $m$ is the electron mass, and $c$ is the speed of light. The parameter $\Theta$ represents the ratio of kinetic and rest energy of the electron and indicates how relativistic the electron speed distribution is. If MJ distribution~\ref{eqa:MJ} is evaluated in normalised speed $\beta$ it’s support is limited to an interval $\left[0,1\right[$. It describes the probability of finding a particle in a hot gas (at temperature $T$) with specific momentum $\textbf{u}$.

The Model

A GAN framework consists of two competing neural networks:

- The Generator (G): Acts like a counterfeiter, learning to produce synthetic data (in our case, samples from a distribution) that looks real.

- The Discriminator (D): Acts like the police, tasked with learning to distinguish between real data and the generator’s synthetic fakes.

This competition drives both models to improve. The generator gets better at making fakes, and the discriminator gets better at distinguishing. The process continues until (hopefully) the generator’s synthetic data is statistically indistinguishable from the real data.

The discriminator seeks to maximise the following expression:

$$ \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n\bigg[log(D(x^{(i)}))+ log(1-D(G(z^{(i)})))\bigg] . $$The discriminator is trained to maximize the average of the log probability for real data and the log of the inverted probabilities of fake data. The generator seeks to minimise the following expression:

$$ \frac{1}{m}\sum_{i=1}^m log(1-D(G(z^{(i)}))) $$Minimising the log of the inverse probability predicted by the discriminator for fake data encourages the generator to generate samples that have a low probability of being fake.

While GANs are powerful, they are difficult to train. It’s common for the discriminator to learn too quickly, leaving the generator unable to learn. Given GAN training is often formulated as a min-max game where we are jointly doing gradient descent over some parameters and ascent over others we end up at a saddle point which is often an unstable loss landscape. Another issue is “mode collapse,” where the generator finds one “fake” sample that works and produces it over and over, rather than learning the full, diverse distribution.

Our Approach & Results

We focused on stabilizing the training process to overcome these challenges. By carefully modifying the training objective and network architecture, we ensured the generator received a strong, consistent learning signal.

This stable approach allowed us to successfully train a GAN to replicate the complex MJ distribution. Our results show that the generated samples are statistically indistinguishable from the true distribution, demonstrating that GANs are a viable and highly efficient alternative to traditional, slow Monte-Carlo sampling in astrophysics.

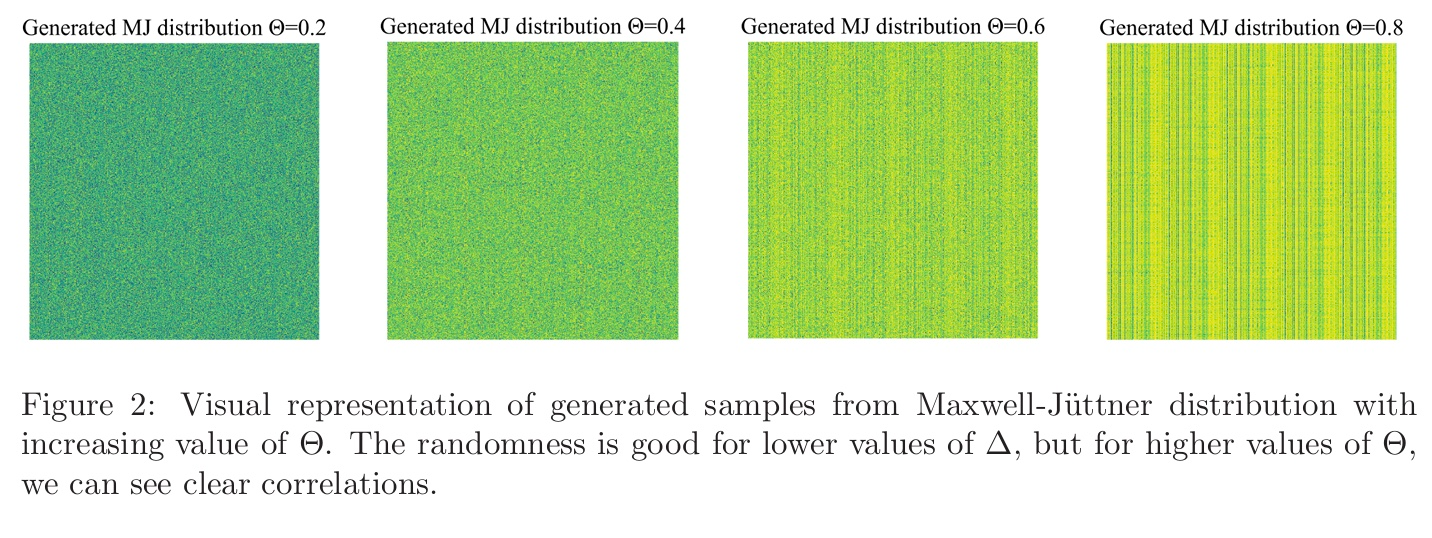

We validated the similarity between generated and true MJ distribution through various statistical tests including the two-sample KS test and the two sample AD test and found generated data was statistically indistinguisable to the true MJ data. Lastly, since we are interesting in generating random variate, we assess the randomness of our generated samples through bitmaps (amongst other statistical tests):

The correlation in generated samples, while those samples pass the KS test, suggests a mode collapse of the generator, where the generator identifies one or few solutions with which it is able to fool the discriminator.

An extension this work to train a CGAN where the temperature is passed in as a hyperparameter so that we learn the full conditional distribution and can load in the random variate from the MJ for a given T.